The Greater Fool Theory refers to a circumstance where an investor purchases an overvalued asset in anticipation that they can sell it for a profit to a "greater fool" who will pay even more. The theory suggests that one can make money from a poor investment, not necessarily due to its fundamental value, but because there is always someone—a greater fool—who is willing to pay a higher price. The term "greater fool theory" is believed to have been popularized in the 20th century, with growing emphasis on speculative trading. It has gained further prominence in periods of significant financial euphoria, including various economic bubbles throughout history, reinforcing its relevance in speculative markets. The Greater Fool Theory emphasizes the potential dangers of speculative bubbles. Awareness of the theory can help investors recognize when asset prices are driven by investors' irrational behavior rather than by intrinsic value. The Greater Fool Theory is founded on two fundamental assumptions. First, it assumes that there will always be someone willing to pay a higher price for an asset, regardless of its intrinsic value. Secondly, it assumes that the investor can sell the asset before its price corrects to reflect its true worth. This essentially means that an investor can profit from overpriced assets as long as there is another investor—a "greater fool"—who is willing to pay an even higher price. This speculative mindset takes precedence over traditional evaluation methods, such as analyzing an asset's fundamentals or inherent value. The Greater Fool Theory underscores the profound influence of investor psychology on financial markets. It is a concept that capitalizes on human behavior, particularly greed and fear, which often supersedes rational decision-making. Investor psychology and herd behavior play significant roles in creating and inflating economic bubbles, as the anticipation of continued price increases causes more and more people to buy, further inflating the price. The fear of missing out, or FOMO, can fuel the speculation, further illustrating the psychological factors behind the Greater Fool Theory. The Greater Fool Theory is intrinsically linked to the creation of speculative bubbles. During such periods, prices skyrocket, often detaching from fundamental values due to the mass optimism of investors who believe they can sell the asset to someone else at an even higher price. Market dynamics under the Greater Fool Theory often involve unsustainable rapid price growth, fueled by investor exuberance, followed by a sharp crash when the bubble bursts. This sequence can be traced in multiple historical financial bubbles, underscoring the theory's relevance in understanding market dynamics. The Greater Fool Theory revolves around the irrational behavior of market participants. While traditional financial theory assumes market participants act rationally, the Greater Fool Theory highlights the fact that this is not always the case. In fact, the theory relies on a degree of irrationality. The "greater fool" in this context is an investor who irrationally buys an overvalued asset with the belief they can sell it at an even higher price. While this may work for a time, it is a strategy built on shaky foundations of market irrationality. A key aspect of the Greater Fool Theory is the focus on short-term gains, often at the expense of fundamental value. Investors operating under this theory tend to disregard fundamentals such as earnings, dividends, or economic indicators, focusing instead on short-term price movements and market sentiment. This approach contradicts traditional investment strategies that prioritize an asset's intrinsic value, and it involves a higher degree of risk due to the volatile nature of speculative markets and the disregard for underlying financial health. The success of the Greater Fool Theory hinges on finding a "greater fool" willing to pay a higher price for an overvalued asset. This feature emphasizes the speculative nature of the theory and its reliance on market sentiment rather than asset fundamentals. Finding a "greater fool" becomes increasingly difficult as the price of an asset rises beyond its intrinsic value, leading to the eventual burst of the speculative bubble. When the supply of "greater fools" runs out, prices often crash, resulting in significant losses for those left holding overpriced assets. One of the strengths of the Greater Fool Theory lies in its ability to exploit market dynamics and momentum. In a bullish market, where prices are on the rise, investors can make substantial profits by riding the wave of optimism and then selling the assets to other buyers at inflated prices. This approach can work particularly well during periods of economic boom or heightened market exuberance when prices tend to rise rapidly. However, it requires a keen sense of timing and an understanding of market sentiment, as the success of this strategy depends on exiting before the bubble bursts. Investing based on the Greater Fool Theory can result in significant financial gains, especially in speculative markets or during periods of economic bubbles. As prices rise, the potential for profit increases, providing opportunities for astute or fortunate investors to make a substantial return on their investments. It is essential, however, to understand that these gains are often short-term and can disappear rapidly if the market turns. Thus, while the potential for profit is a strength of the Greater Fool Theory, it comes with a commensurate level of risk. Rather than focusing on fundamentals, which can require deep knowledge and extensive research, this theory allows for investment decisions based on market sentiment and price trends. This flexibility can be attractive, especially to novice investors or those who prefer a more speculative approach. However, it's crucial to note that this kind of investing can be risky and requires careful monitoring of market conditions. One of the main limitations of the Greater Fool Theory is its lack of sustainability in the long run. The theory relies on continually finding someone willing to pay more for an asset, which becomes increasingly difficult as the price escalates far beyond the asset's intrinsic value. Once prices peak and start to fall, they often do so rapidly and drastically, leaving late investors with significant losses. Therefore, the Greater Fool Theory is not a sustainable strategy for long-term investing. While the theory can lead to substantial gains in a rising market, the reverse is also true. If an investor is unable to sell an overvalued asset before the market corrects, they can be left holding assets worth significantly less than they paid for them. Moreover, because this theory is based on speculation rather than fundamental analysis, it can lead to more significant losses when the market turns. This potential for substantial losses makes the Greater Fool Theory a high-risk investment strategy. The Greater Fool Theory can also have negative implications for market stability and investor confidence. By fueling speculative bubbles, it can contribute to market volatility and financial instability. When a bubble bursts, not only do many investors incur losses, but trust in the market can also be eroded, making people less likely to invest in the future. This can have long-term consequences for the health and stability of financial markets. By spreading investments across a variety of assets, sectors, and geographic locations, investors can reduce their exposure to any single investment and thus lessen the potential impact of a market downturn. Diversification can help insulate an investment portfolio from the effects of a speculative bubble, making it a useful strategy for those who wish to guard against the risks of the Greater Fool Theory. Fundamental analysis involves evaluating an asset's intrinsic value by examining related economic, financial, and other qualitative and quantitative factors. This can include analysis of financial statements, market conditions, industry trends, and economic indicators. By using fundamental analysis, investors can make more informed decisions and potentially avoid overvalued assets, thus minimizing the risk associated with the Greater Fool Theory. This approach stands in stark contrast to the speculation that characterizes the Greater Fool Theory, offering a more stable and sustainable investment strategy. This could include setting stop-loss orders to limit potential losses, monitoring market trends closely, and being ready to adjust your investment strategy as necessary. Effective risk management can help protect against significant losses, especially in volatile or speculative markets where the Greater Fool Theory is at play. Adopting a long-term investment approach can also guard against the risks of the Greater Fool Theory. Rather than seeking quick profits, long-term investing focuses on gradual wealth accumulation over an extended period. This strategy often involves investing in high-quality assets that have the potential for growth over time, rather than speculative assets that may be overvalued. This approach can provide a more stable and reliable return on investment, reducing the risks associated with speculative investing and the Greater Fool Theory. One of the earliest and most famous examples of the Greater Fool Theory in practice is the Dutch Tulip Mania in the 17th century. During this period, prices for tulip bulbs skyrocketed due to rampant speculation, with some bulbs selling for more than the price of a house. However, the bubble eventually burst when it became clear that the prices did not reflect the intrinsic value of the bulbs, leading to a market crash. This serves as a classic example of the Greater Fool Theory, where people were willing to pay exorbitant prices based on the belief that they could sell the bulbs to a "greater fool" for an even higher price. During this time, speculation around the potential of the internet drove the stock prices of tech companies to unprecedented heights, often regardless of their profitability or business model. However, when the bubble burst in the early 2000s, many of these companies' stocks crashed, leading to substantial losses for investors who had bought in at the height of the bubble. This serves as a stark reminder of the risks associated with the Greater Fool Theory and the potential for significant losses when speculative bubbles burst. The housing bubble and subsequent subprime mortgage crisis in 2008 also reflect the Greater Fool Theory. Leading up to the crisis, home prices were rising rapidly due to speculative buying, often funded by risky mortgage loans. When the bubble burst, home prices fell dramatically, leaving many homeowners with mortgages larger than their homes' worth. This led to widespread foreclosures and a global financial crisis, underlining the potential for the Greater Fool Theory to contribute to broader economic instability. The Greater Fool Theory is a concept in finance that suggests investors can profit by purchasing overvalued assets with the expectation of selling them to a "greater fool" who is willing to pay an even higher price. It recognizes the influence of market dynamics and momentum on asset prices and emphasizes the role of investor behavior and psychology in driving market trends. The theory is based on the assumption that market participants can be irrational and driven by short-term gains, disregarding fundamental factors. It has been observed in historical examples such as tulip mania, the dot-com bubble, and the housing bubble. The theory has strengths, including potential short-term gains and flexibility in investment strategies. However, it has limitations, lacking long-term sustainability and carrying the risk of significant losses. To mitigate risks, diversify investments, conduct fundamental analysis, implement risk management techniques, adopt a long-term approach, seek professional advice, and monitor portfolios.What is the Greater Fool Theory?

Explanation of the Greater Fool Theory

Basic Principles and Assumptions

Role of Investor Behavior and Psychology

Connection to Speculative Bubbles and Market Dynamics

Key Features of the Greater Fool Theory

Rationality and Irrationality of Market Participants

Focus on Short-Term Gains and Disregarding Fundamentals

Dependence on Finding a "Greater Fool" to Sell Assets at a Higher Price

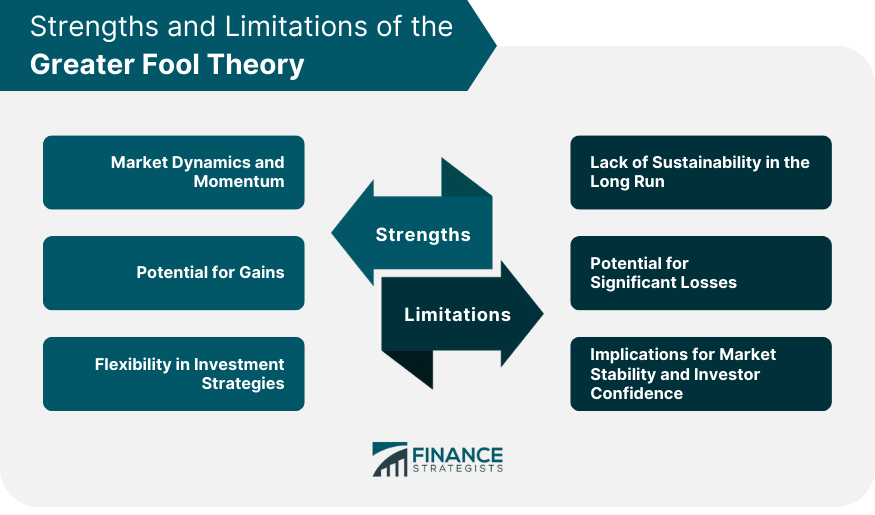

Strengths of the Greater Fool Theory

Market Dynamics and Momentum

Potential for Gains

Flexibility in Investment Strategies

Limitations of the Greater Fool Theory

Lack of Sustainability in the Long Run

Potential for Significant Losses

Implications for Market Stability and Investor Confidence

Strategies to Mitigate Risks Associated With the Greater Fool Theory

Diversification

Fundamental Analysis

Risk Management Techniques

Long-Term Investment Approach

Examples of the Greater Fool Theory in Practice

Tulip Mania in the 17th Century

Dot-Com Bubble in the Late 1990s

Housing Bubble and Subprime Mortgage Crisis in 2008

Conclusion

Greater Fool Theory FAQs

The Greater Fool Theory is a financial concept that suggests an investor can profit from buying overvalued assets, provided they can sell them to a "greater fool" who is willing to pay an even higher price.

The main risk of the Greater Fool Theory is the potential for significant losses if the investor is unable to sell the overvalued asset before its price corrects to reflect its intrinsic value. This can lead to substantial financial losses, especially during a market downturn or when a speculative bubble bursts.

Strategies that can help mitigate the risks associated with the Greater Fool Theory include diversification, fundamental analysis, risk management techniques, and adopting a long-term investment approach.

Historical examples of the Greater Fool Theory in action include Tulip Mania in the 17th century, the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s, and the housing bubble and subprime mortgage crisis in 2008. In each of these cases, rampant speculation led to inflated asset prices, which eventually crashed when the supply of "greater fools" ran out.

While the Greater Fool Theory can result in significant gains during a bullish market, it is not a reliable or sustainable investment strategy. It relies on irrational behavior and speculation rather than fundamental analysis, making it a high-risk strategy that can lead to substantial losses.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.