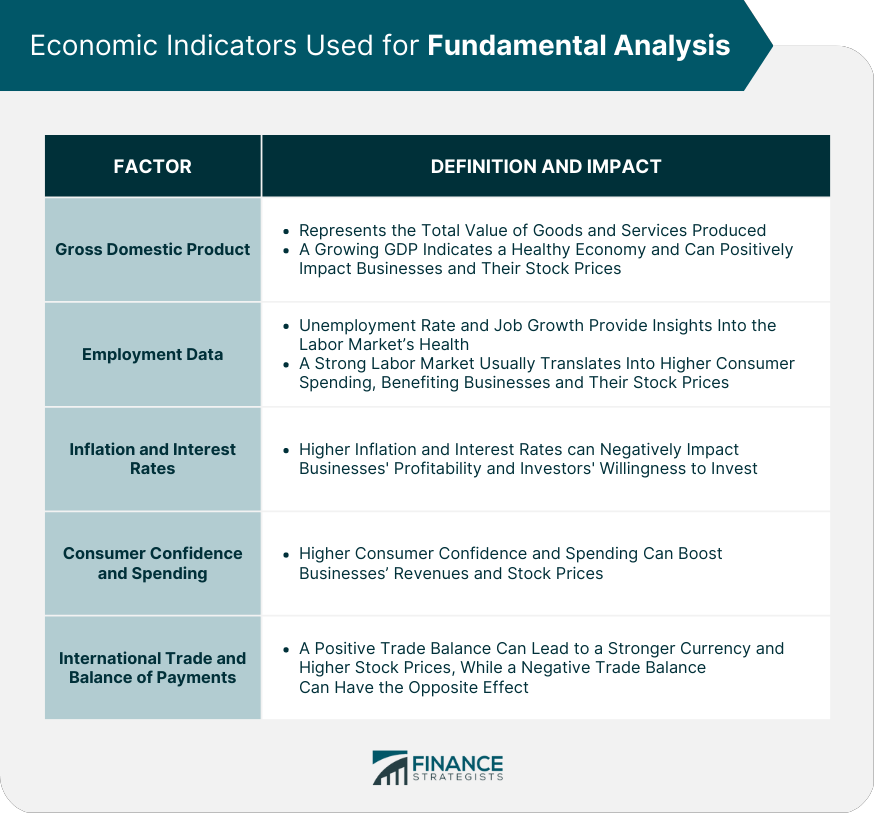

Fundamental analysis is a method of evaluating the intrinsic value of a security or an asset by analyzing various economic, financial, and qualitative factors that can affect the asset's value over the long term. This approach involves looking at factors such as the company's financial statements, industry trends, management quality, and macroeconomic conditions to determine the asset's potential for growth and its fair market value. The goal of fundamental analysis is to identify investments that are undervalued or overvalued based on their intrinsic value, and to make informed investment decisions based on this analysis. Economic indicators are vital tools that help investors gauge the overall health of an economy and make informed investment decisions. Some of the key economic indicators include: GDP represents the total value of goods and services produced in a country over a specific period. A growing GDP indicates a healthy economy and can positively impact the performance of businesses and, consequently, their stock prices. Employment data, such as the unemployment rate and job growth, provide insights into the labor market's health. A strong labor market usually translates into higher consumer spending, benefiting businesses and their stock prices. Inflation measures the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, while interest rates represent the cost of borrowing money. Both factors can influence stock prices, as higher inflation and interest rates can negatively impact businesses' profitability and investors' willingness to invest. Consumer confidence measures consumers' optimism about the economy and their financial situation, which influences their spending habits. Higher consumer confidence and spending can boost businesses' revenues and stock prices. International trade and the balance of payments provide insights into a country's trade relationships and the overall health of its economy. A positive trade balance can lead to a stronger currency and higher stock prices, while a negative trade balance can have the opposite effect. Before evaluating individual companies, it's essential to analyze the industries and sectors in which they operate. This includes understanding the competitive landscape, growth potential, and industry-specific metrics. Porter's Five Forces Model is a framework developed by Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter to analyze the competitive forces that shape industries and companies. The model identifies and analyzes five competitive forces that determine the level of competition and attractiveness of an industry or market. These five forces include the bargaining power of suppliers, the bargaining power of buyers, the threat of new entrants, the threat of substitute products or services, and the intensity of competitive rivalry. The model is widely used in business strategy to assess the potential profitability of an industry and develop effective competitive strategies. The industry life cycle refers to the stages an industry goes through, from inception to maturity and, eventually, decline. Understanding the life cycle stage can help investors identify the growth potential and risks associated with a particular industry. Industry-specific metrics are vital for understanding the performance and financial health of companies operating within a specific industry. Examples include same-store sales for retail, average revenue per user (ARPU) for telecommunications, and occupancy rates for real estate. After examining the industry, it's crucial to analyze individual companies to determine their financial health, competitive advantages, and growth prospects. Investors can assess a company's financial health and performance by analyzing its financial statements, which include the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement. Financial ratios are tools used by investors, analysts, and managers to evaluate the financial health and performance of a company. These ratios are calculated by comparing different financial metrics from a company's financial statements, such as the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement. Financial ratios can provide insights into a company's profitability, liquidity, solvency, and efficiency. Some common types of financial ratios include profitability ratios (e.g., return on investment), liquidity ratios (e.g., current ratio), solvency ratios (e.g., debt-to-equity ratio), and efficiency ratios (e.g., inventory turnover). By analyzing these ratios, investors and managers can gain a better understanding of a company's financial strengths and weaknesses, and make informed decisions about investments and operations. SWOT analysis is a strategic planning tool that helps businesses identify their internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats. The acronym SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. Strengths and weaknesses refer to the internal factors of a business, such as its resources, capabilities, and performance, that can affect its competitiveness and success. Opportunities and threats refer to the external factors that are outside the control of a business, such as market trends, industry competition, and regulatory changes, that can impact its operations and growth potential. By conducting a SWOT analysis, businesses can gain a comprehensive understanding of their position in the market and develop effective strategies to leverage their strengths, address their weaknesses, capitalize on opportunities, and mitigate threats. This analysis can be used for a wide range of applications, including business planning, marketing strategy, product development, and risk management. Evaluating a company's management team and corporate governance practices is essential to understand its ability to navigate challenges and capitalize on opportunities. Effective management and good corporate governance can positively influence a company's performance and stock price. A competitive advantage, or moat, is a unique attribute that sets a company apart from its competitors and allows it to maintain its market position. Examples of competitive advantages include economies of scale, brand recognition, and proprietary technology. Valuation techniques are methods used to estimate the intrinsic value of a security. Some popular valuation techniques include: DCF analysis estimates the value of an investment based on its expected future cash flows, discounted back to their present value using an appropriate discount rate. The P/E ratio compares a company's stock price to its earnings per share (EPS), providing insights into the relative valuation of a company compared to its peers. The P/S ratio compares a company's stock price to its revenue per share, offering another measure of relative valuation. The P/B ratio compares a company's stock price to its book value per share, reflecting the market's valuation of a company's net assets. The DDM is a valuation method specifically for dividend-paying stocks, estimating the value of a stock based on the present value of its future dividend payments. Relative valuation involves comparing a company's valuation ratios to those of other companies within the same industry, providing a benchmark for assessing whether a stock is undervalued or overvalued. Investors can integrate fundamental analysis into various investment strategies, such as: Value investing focuses on identifying undervalued securities by comparing their intrinsic value to their market price, with the expectation that the market price will eventually reflect the intrinsic value. Growth investing involves identifying companies with above-average growth potential, often characterized by rapidly expanding revenues, earnings, or market share. Income investing targets stocks that pay consistent and growing dividends, providing investors with a steady stream of income and potential capital appreciation. Contrarian investing involves going against prevailing market trends, buying undervalued stocks when others are selling and selling overvalued stocks when others are buying. Quality investing focuses on companies with strong fundamentals, such as robust profitability, low debt levels, and effective management teams, which are expected to outperform the market over the long term. Despite its usefulness, fundamental analysis has certain limitations and challenges, including: Fundamental analysis often involves making subjective judgments based on qualitative and quantitative data, which can lead to different conclusions among investors. Market sentiment and psychology can sometimes overshadow fundamentals, causing stock prices to deviate from their intrinsic value for extended periods. Macroeconomic factors, such as political events, natural disasters, and global economic trends, can influence stock prices and make it difficult for investors to accurately assess a company's intrinsic value. Fundamental analysis can be time-consuming, as it requires a thorough understanding of various economic, industry, and company-specific factors. Fundamental analysis is an essential tool for making informed investment decisions, as it helps investors assess the intrinsic value of securities by examining various economic, industry, and company-specific factors. By understanding the competitive landscape, financial health, and growth prospects of companies, investors can identify undervalued or overvalued securities and integrate fundamental analysis into their investment strategies. While fundamental analysis has its limitations and challenges, such as subjectivity and the influence of market sentiment, it remains a critical component of a balanced investment approach. To maximize its benefits, investors should continuously update their analysis and knowledge of relevant factors, adapting their strategies as market conditions and company fundamentals evolve. Ultimately, fundamental analysis can help investors build a diversified and well-informed portfolio, increasing the likelihood of long-term success in the financial markets.What Is Fundamental Analysis?

Economic Indicators

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Employment Data

Inflation and Interest Rates

Consumer Confidence and Spending

International Trade and Balance of Payments

Industry Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Model

Industry Life Cycle

Key Industry-Specific Metrics

Company Analysis

Financial Statement Analysis

Financial Ratios

SWOT Analysis

Management and Corporate Governance

Competitive Advantages and Moats

Valuation Techniques

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Analysis

Price-To-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

Price-To-Sales (P/S) Ratio

Price-To-Book (P/B) Ratio

Dividend Discount Model (DDM)

Relative Valuation and Comparables

Integrating Fundamental Analysis Into Investment Strategies

Value Investing

Growth Investing

Income Investing

Contrarian Investing

Quality Investing

Limitations and Challenges of Fundamental Analysis

Subjectivity in Analysis and Interpretation

Influence of Market Sentiment and Psychology

Impact of Macroeconomic Factors

Time-Consuming Nature of the Process

Conclusion

Fundamental Analysis FAQs

Fundamental analysis is a method of evaluating a security or an asset by examining its intrinsic value. This involves analyzing various economic, financial, and qualitative factors that affect the underlying asset, such as earnings, revenue, management quality, industry trends, and macroeconomic conditions.

Fundamental analysis is focused on the underlying economic and financial factors that influence an asset's value, while technical analysis is concerned with analyzing the historical price and volume data to identify patterns and trends that can be used to predict future price movements.

The key components of fundamental analysis include financial statements, economic indicators, industry trends, and qualitative factors such as management quality, brand value, and competitive advantage. These factors are analyzed to determine the intrinsic value of the asset and its potential for growth.

Analysts use fundamental analysis to evaluate the potential of a security or an asset and make investment decisions based on their assessment of the asset's intrinsic value. They look at various factors such as the company's financial health, growth prospects, and competitive position to determine whether the asset is undervalued, overvalued, or fairly valued.

Fundamental analysis is subject to various limitations, such as the accuracy and reliability of the financial statements, the impact of unforeseen events, and the complexity of some industries. Additionally, fundamental analysis does not take into account short-term market fluctuations or investor sentiment, which can impact the asset's value.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.