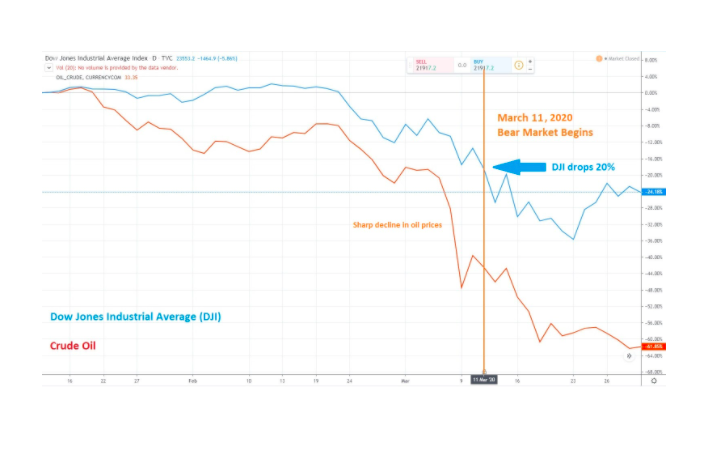

A bear market refers to a market state characterized by falling securities prices and pessimistic investor sentiment. A market space is considered to be experiencing a bear run if the prices of securities fall 20% or more from their previous high. During a bear market, investors are not confident that the market will soon experience an upturn, and so many will sell off their stocks to avoid incurring a loss while the price drops. As more investors sell, prices drop even further, initiating a vicious selling cycle which feeds on itself and drives prices down even more. The first bear market of the millennium followed an unprecedented boom in the IT sector. During the dotcom boom, many emerging technology companies, largely funded by venture capital, began to dominate the stock market, with shares of companies like MicroStrategy rising in price from around $7 to over $300 over the course of a single year. This was to be the status quo in the IT sector until late 1999 when mounting fears over the "Y2K" bug began to erode investor confidence. While concerns over this glitch turned out to be unfounded, it was followed shortly by an increase in interest rates announced in February by Alan Greenspan. It was unclear for investors how well IT companies would be able to cope with this increase. A recession in Japan on March 13, 2000 triggered a mass sell off of stocks in the US that disproportionately affected the IT sector. On March 20 of that year, Barron's magazine published an article predicting the imminent bankruptcy of IT companies. That same day, MicroStrategy announced that share prices fell from around $333 to $140, a 62% drop over a single day. By the end of March, increased interest rates led to an inverted yield curve, and on April 3 many of the largest IT corporations, such as Microsoft, began running into legal trouble. Microsoft in particular was ruled to have committed monopolization and tying practices. By November 9, most IT stocks had lost 75% of their value, and by the end of 2002, over $5 trillion in value had been erased. The timeline of this bear run shows the degree to which investor psychology can affect the market. The 2007-2008 financial crisis was initiated when NewCentury, an American REIT specializing in subprime mortgages, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Subprime lending is a practice whereby lenders allow high-risk borrowers with poor credit quality to take out loans at high interest rates and with unfavorable terms benefitting the lender. Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection gave NewCentury temporary court protection from debtors while they attempted to restructure their finances to pay their debts. Following this, BNP Paribas blocked withdrawal from three of its hedge funds, sparking concerns over liquidity. This would also start off a halt of interbank lending as banks worldwide ceased doing business with each other. In response to concerns over liquidity, the Federal Open Market Committee reduced the federal funds rate from its previous peak of 5.25%. On July 30, 2008, the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 was passed, allowing the government to guarantee (or assume the debt in case of default) up to $300 billion in fixed rate 30 year mortgages for subprime borrowers, provided that lenders wrote down principal loan balances to 90% of current appraisal value. The month of September in 2008 saw Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae taken over by the government, as well as widespread bankruptcy, restructuring, and acquisitions among banks. On September 29, the House of Representatives rejected the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, instead instituting the Troubled Asset Relief Program. In response to this, the Dow Jones dropped over 777 points, and on October 3 the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act passed. On December 16, the federal funds rate was reduced to 0%, a low which would not be seen again until the 2020 stock market crash caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2020 crash succeeded a bull run of 11 years, the longest in US history. On February 12, 2020, the DJIA, NASDAQ, and S&P 500 indices all finished with record highs. Between this time and February 20, Coronavirus had begun to have a significant economic impact on Asian-Pacific markets, with the People's Bank of China cutting its repo rates by 10 points. From February 20 to March 11, the DJI fell by 20% off its recent high set only one month earlier. On the same day, President Donald Trump announced a 30 day travel ban on non US citizens who had recently been to the Schengen area of Europe. While the terms of this ban were later clarified to not include trade restrictions with those countries, investors nonetheless felt the sword of Damocles about to fall. The next day, both the NASDAQ Composite and the S&P 500 joined the DJI in falling 20% off their recent highs, facilitating the most significant market crash since 1987. Through the remainder of March, the DJI, NASDAQ, and S&P 500 continued to fall in excess of 10%, while oil prices plummeted by 24%, an 18-year low. The larger stock market has since seen a small uptick after the proposition of a $2 trillion stimulus bill that is currently moving through congress. As of March 31, however, the DJI closed with its worst single quarter decline in history, joined by oil prices which also experienced their worst single quarter decline in history. The chart below shows the drop in the Dow Jones and the price of oil following the market's historic bull run. Bear markets should not be confused with corrections, which are short term economic declines of 10% to 20%. Fluctuations like these are common, even in healthy markets, and can provide points of entry for new investors to take advantage of temporary price drops. Bear markets indicate a more serious problem for the economy, and new investors would be wise to avoid getting involved during one. Bear markets don't have predictable bottoms, so it can be hard to tell when one will end or how bad it will be. Because of how important investor psychology is in determining market trends, some prefer to define a bear market as a period in which the majority of investors are risk-averse as opposed to risk-tolerant, as is the case during bull markets. When the entire market space is "bearish" or "bullish" it indicates the prevailing mindset of all investors. Like bull markets, bear markets are a self-fulfilling prophecy. If enough investors believe that a bear run is imminent, they will begin selling en masse, dropping prices and triggering the market state they predicted. Bear markets end when prices fall so low that investors begin to buy again, hoping to profit once the price increases. As more investors buy stock prices invariably do increase, and the bear market ends. As an investor, you can still make money in a bear market by short selling stocks. Short selling is a technique in which a stock owner borrows shares from a broker, sells them anticipating a price drop, and then buys them back for less after the price decreases. The profit an investor makes is determined by the difference between the selling price and the repurchase price, times the number of shares sold. For example, if an investor sells 100 shares at $90 each and then buys them back later for $80 each, they have made a profit of $10 times 100, or $1000. This is a high-risk practice because it relies on the price of the stock continuing to fall. If an investor miscalculates and has to buy back the stocks at a higher price, they could lose significant amounts of money. Using the same formula, if an investor sells 100 shares for $90 each and then has to repurchase them for $110 each, they will lose $20 times 100, or $2000.Quick Definition

2000 Dotcom Crash

2008 Subprime Lending Crash

COVID-19 2020 Market Crash

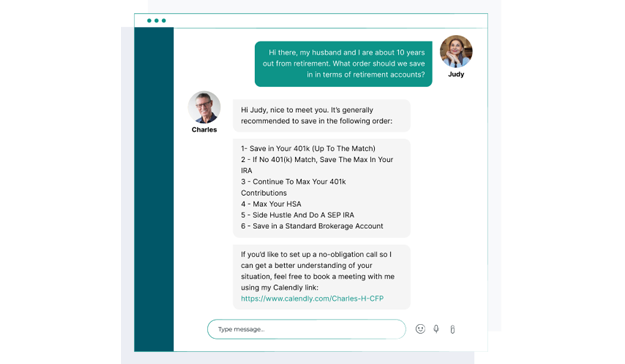

Can Investors Make Money in a Bear Market? (PRO TIP)

Bear Market FAQs

A bear market refers to a market state characterized by falling securities prices that drop by more than 20% from their previous high and is accompanied by pessimistic investor sentiment.

Bear markets should not be confused with corrections, which are short term economic declines of 10% to 20%.

Bear markets end when prices fall so low that investors begin to buy again. As more investors buy, stock prices increase, and the bear market ends.

The 2007-2008 financial crisis was initiated when NewCentury, an American REIT specializing in subprime mortgages, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, which caused a bear market.

Investors can still make money in a bear market by short selling stocks. Short selling is a technique in which a stock owner borrows shares from a broker, sells them anticipating a price drop, and then buys them back for less after the price declines. Profit is determined by the difference between the sell price and the repurchase price.

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide, a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University, where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon, Nasdaq and Forbes.